Joseph Cornell’s Dreams

Joseph Cornell

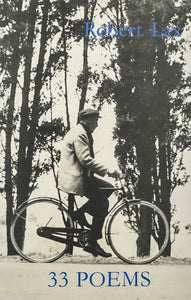

Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) is known for the oneiric quality of his art and films. Some of our greatest poets have worked to describe the strange power of his boxes, toy-like constructions whose playfulness and humor are anchored in a profound melancholy and loneliness. “Slot machine of visions,” wrote Octavio Paz. Cornell himself is said to have enjoyed children’s responses to his work best; perhaps because nothing prepares one for viewing a Cornell box, other than paying attention to one’s dreams. Catherine Corman has combed through Cornell’s voluminous diaries, now in the care of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, in search of the artist’s own dreams. What she found are flashes of images and short, enigmatic narratives of illumination — the verbal equivalent of Cornell boxes. As she writes, “The dreams are not derived from waking life, but appear as if by chance. Cornell spends the day eating pastries and riding a bicycle. Falling asleep on the couch is like pulling the lever of the slot machine of visions. Images of naiads, lambs, and the ocean appear.”